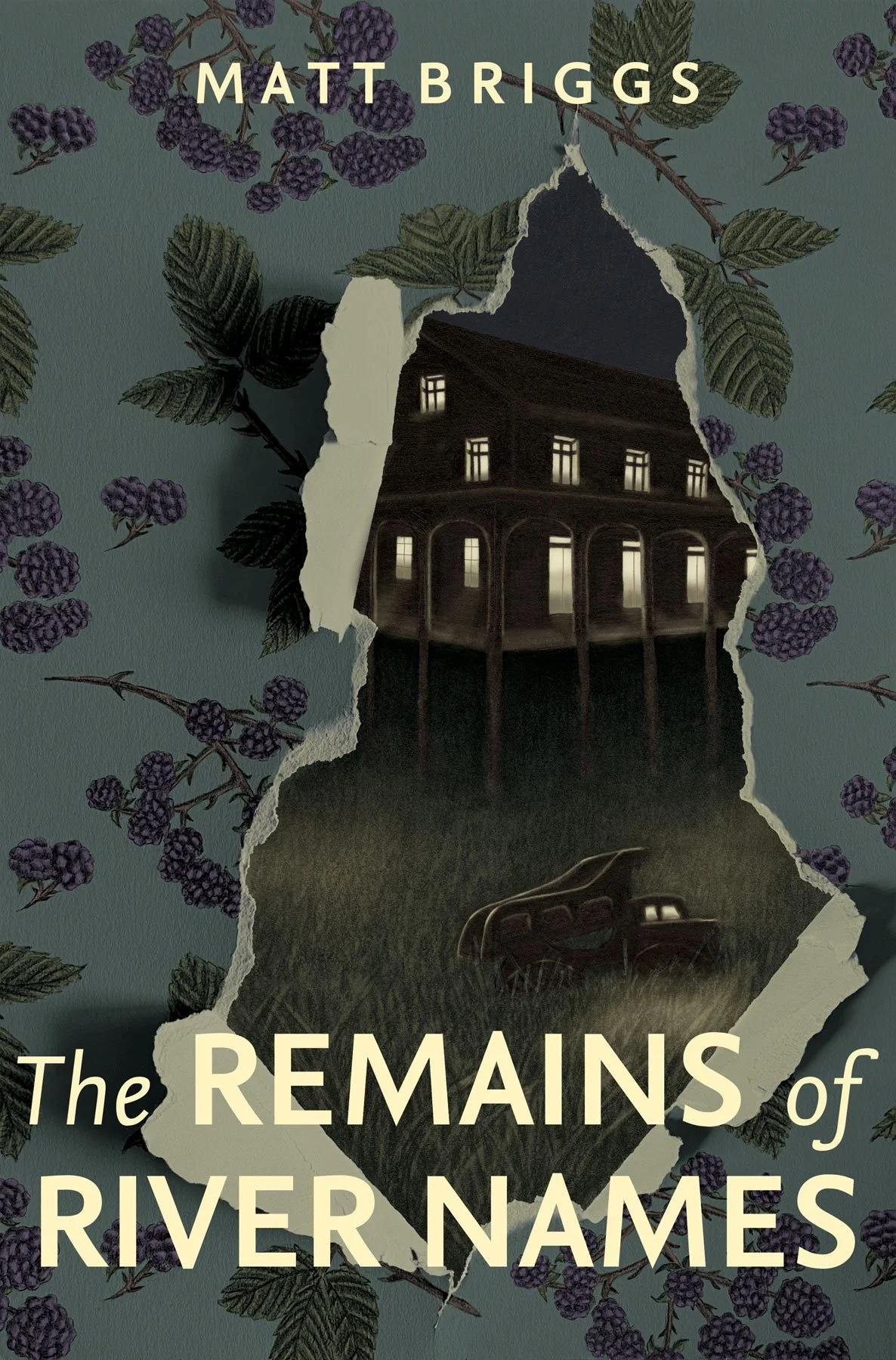

The Remains of River Names eBook by Matt Briggs

Winner of the King County Arts Commission Publication Prize, 1998

Briggs’ novel opens with Artie and Janice Graham, former hippies, fleeing as the police close in on their marijuana farm. They show little remorse at leaving their two school-aged sons behind to fend for themselves. These former flower children possess no ideals or purpose and live for the moment through the fifteen-year span of the novel, while their children, trapped in a cycle of selfishness, become isolated and antisocial. As adults, they separately commit assault, drunk driving, and attempted rape.

“Abstract words like sacrifice or hallow are barren beside the concrete names of rivers and mountains like Snoqualmie, Snohomish,” Briggs writes. Like these rivers, the Grahams are unfeeling and cold, raging and stagnating until the novel’s close. Finally, youngest son Dillon alone pursues redemption by attempting to salvage a damaged relationship with his partner. “You are not just a word or a name,” he says.

While the “dreadful business of living, working, and sleeping makes us prisoners right now,” Briggs demonstrates that life attains meaning when one makes a conscious effort to give of oneself. Powerful in its images, Faulknerian in structure and tone, Briggs’ foreboding portrait of contemporary society is challenging and effective. — Samuel Dempsey

Winner of the King County Arts Commission Publication Prize, 1998

Briggs’ novel opens with Artie and Janice Graham, former hippies, fleeing as the police close in on their marijuana farm. They show little remorse at leaving their two school-aged sons behind to fend for themselves. These former flower children possess no ideals or purpose and live for the moment through the fifteen-year span of the novel, while their children, trapped in a cycle of selfishness, become isolated and antisocial. As adults, they separately commit assault, drunk driving, and attempted rape.

“Abstract words like sacrifice or hallow are barren beside the concrete names of rivers and mountains like Snoqualmie, Snohomish,” Briggs writes. Like these rivers, the Grahams are unfeeling and cold, raging and stagnating until the novel’s close. Finally, youngest son Dillon alone pursues redemption by attempting to salvage a damaged relationship with his partner. “You are not just a word or a name,” he says.

While the “dreadful business of living, working, and sleeping makes us prisoners right now,” Briggs demonstrates that life attains meaning when one makes a conscious effort to give of oneself. Powerful in its images, Faulknerian in structure and tone, Briggs’ foreboding portrait of contemporary society is challenging and effective. — Samuel Dempsey

Winner of the King County Arts Commission Publication Prize, 1998

Briggs’ novel opens with Artie and Janice Graham, former hippies, fleeing as the police close in on their marijuana farm. They show little remorse at leaving their two school-aged sons behind to fend for themselves. These former flower children possess no ideals or purpose and live for the moment through the fifteen-year span of the novel, while their children, trapped in a cycle of selfishness, become isolated and antisocial. As adults, they separately commit assault, drunk driving, and attempted rape.

“Abstract words like sacrifice or hallow are barren beside the concrete names of rivers and mountains like Snoqualmie, Snohomish,” Briggs writes. Like these rivers, the Grahams are unfeeling and cold, raging and stagnating until the novel’s close. Finally, youngest son Dillon alone pursues redemption by attempting to salvage a damaged relationship with his partner. “You are not just a word or a name,” he says.

While the “dreadful business of living, working, and sleeping makes us prisoners right now,” Briggs demonstrates that life attains meaning when one makes a conscious effort to give of oneself. Powerful in its images, Faulknerian in structure and tone, Briggs’ foreboding portrait of contemporary society is challenging and effective. — Samuel Dempsey